A version of this article originally appeared in the Santa Barbara Independent

Early Days

Courtesy of Sam Spaulding

For time immemorial, the Santa Ynez Valley has been home to the Chumash peoples, many of whom utilized the land and natural resources in the place that is now Sedgwick Reserve. The Valley, abundant in food, fuel, and building materials, enabled a vast population of Chumash who supplemented what was available locally through a sophisticated trade network with villages further in the interior, along the coastline, and on the Channel Islands.

In 1769, a Spanish land expedition led by Gaspar de Portola left Baja California and reached the Santa Barbara Channel. In short order, the ancestral land of the Chumash became largely run by the five missions that had been established.

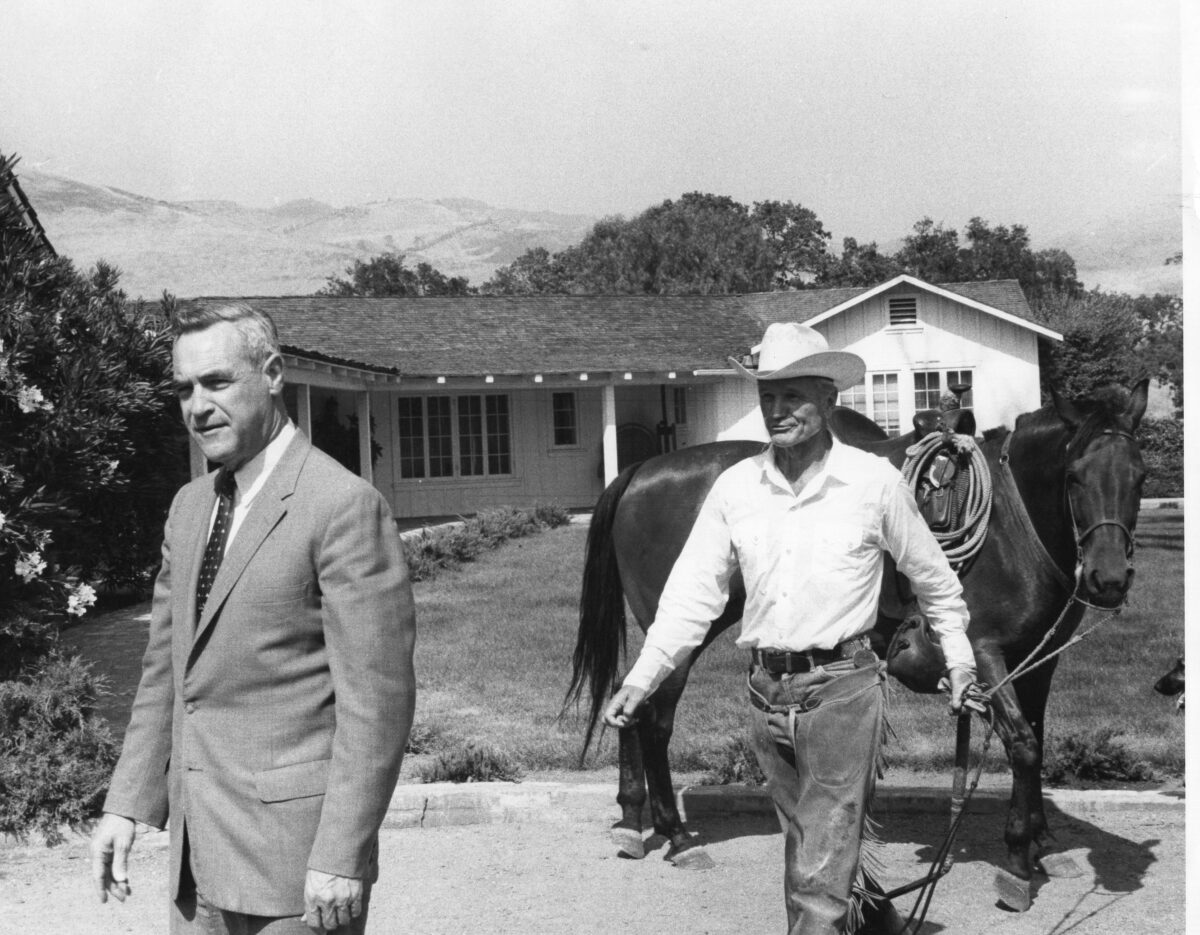

For the next 150 years, Sedgwick Reserve was used for ranching activities, including grazing by livestock. The property went through a series of owners beginning with Octaviano Gutierrez, who acquired it as part of a Mexican land grant. At the time, it was known as Rancho La Laguna. After a series of owners, Francis and Alice Sedgwick purchased the property in 1952.

These were no ordinary ranchers. Francis “Duke” Minturn Sedgwick and his wife Alice de Forest-Sedgwick were both from wealthy New England families. Both were passionate about the arts. Duke was a sculptor, novelist, and art collector; Alice studied piano at the Juilliard School of Music. After 17 years on the ranch, the Sedgwicks donated 51% of the property to the University of California with the pledge that the rest would follow upon their deaths.

Duke died in October 1967 and Alice continued to live on the property until her death in 1988. Despite the couple’s original wishes, Alice decided to leave the remaining 782 acres, including the ranch headquarters, to her five children, and she authorized the University to sell its portion.

Preserving the Whole

The donation of the ranch, valued at $3 million at the time, was the largest single private gift UCSB had received. In the late 1980s, UCSB proposed to sell its piece of the property in part to raise money to build an art museum that would house the Sedgwick Collection. A UCSB professor of ecology, Bruce Mahall, and graduate student, John Cloud, formed the Friends of Sedgwick to advocate for the preservation of the ranch in its entirety, arguing it should be used for scientific research and public enjoyment.

The Land Trust for Santa Barbara County took the lead to resolve the dispute. In 1995 the Land Trust received a lease/option agreement from the Sedgwick Estate that gave the organization a year to purchase the “heirs’ parcel.” An agricultural easement was made by the county for $800,000. The Nature Conservancy kicked in $800,000 for a bridge loan. Other donors included the State Wildlife Conservation Board, the Lennox Foundation, the Towbes Foundation, the State’s Environmental Enhancement and Mitigation Program, the Irvine Foundation, and local individuals. Even with all the contributions, the Land Trust was still $85,000 short, but the deadline was ultimately met as neighbors delivered the final sum.

In 1997, full ownership was transferred to the UC Natural Reserve System, marking the establishment of the nearly 6,000-acre Sedgwick Reserve as it exists today. The Land Trust, led by David Anderson, deserves the community’s thanks for a difficult job well done. The “Anderson Overlook” at the property, which is arguably one of its grandest vista-points, was named in his honor.

Off and Running

Within a year of the reserve’s formation, at least 20 research projects were already underway. This included a long-term effort by UCSB faculty Bruce Mahall, Claudia Tyler, and Frank Davis to understand the iconic oak ecosystems of California, which continues today and has significantly advanced understandings of oak mortality.

The property’s primary buildings at the time included the historic “Rancho La Laguna” barn built in 1908, the Ranch House built in 1947, various buildings for the Sedgwick family and staff, and an art studio. Over the last 25 years, these buildings have been renovated through state and private funding to better host researchers, classes, and the public. Through the support of Linda La Kretz-Duttenhaver, the Barn was renovated in 2009 and the Ranch House in 2018. Careful attention was paid to maintain the historic character of the structures.

In 2011, the Tipton Meeting House was built. It is one of few LEED Platinum-rated buildings in the UC System. And in 2017, the philanthropically endowed La Kretz Center for Research at Sedgwick Reserve was established with UCSB Professor Frank Davis as its inaugural director.

A Mecca for Science

At any given time, Sedgwick Reserve is home to dozens of research projects. While many are led by UCSB faculty and students, it is not uncommon for researchers to fly in from other states and countries to conduct their work. Every year, an average of 10-25 peer-reviewed manuscripts are published that utilize research done at Sedgwick with emphasis on climate, biodiversity, wildfire, and remote sensing, including an ongoing project with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. A fire ecology and prescribed-burn research program has also been “heating up” since 2017, with the first prescribed burn conducted in Sedgwick grassland in late 2020.

Sedgwick Reserve hosts up to two dozen university-level class visits each year that focus on biology, physical science, environmental management, social science, art, and education. While most classes come for just the day, the Field Station provides a place for students to stay overnight, with many experiencing camping for the very first time.

Outreach has always been an important part of Sedgwick’s mission. Schools send their students for regular field trips, and the Reserve hosts an average of 300 K-12 students every year. In 2001, the first docent training took place and has continued ever since. Some members of the inaugural class still lead hikes, workshops, and community events to this day.

Volunteers maintain a native plant nursery on the property, support demonstration gardens and restoration projects, clear trails and maintain facilities, take part in citizen science monitoring, and contribute thousands of hours of service annually to the Reserve.